John Locke’s Theory of Knowledge

(An Essay Concerning Human Understanding)

by Caspar Hewett

John Locke’s epistemology by Casper Hewitt

Click Here for printable version of this page

Published in 1690, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

is the masterwork of the great philosopher of freedom John Locke. Nearly twenty

years in preparation Locke began working on The

Essay in 1670 following a series of philosophical

discussion during which he and his friends decided that “it was necessary to

examine our own abilities, and see what objects our understandings were, or

were not, fitted to deal with.” The Essay is an

attempt to establish what it is and isn’t possible for us to know and

understand. “My purpose” Locke says, is “to enquire into the origin, certainty,

and extent of human knowledge; together, with the grounds and degrees of

belief, opinion, and assent.” The aim thus is not to achieve certainty, but to

understand how much weight we can assign to different types of knowledge.

Published in 1690, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

is the masterwork of the great philosopher of freedom John Locke. Nearly twenty

years in preparation Locke began working on The

Essay in 1670 following a series of philosophical

discussion during which he and his friends decided that “it was necessary to

examine our own abilities, and see what objects our understandings were, or

were not, fitted to deal with.” The Essay is an

attempt to establish what it is and isn’t possible for us to know and

understand. “My purpose” Locke says, is “to enquire into the origin, certainty,

and extent of human knowledge; together, with the grounds and degrees of

belief, opinion, and assent.” The aim thus is not to achieve certainty, but to

understand how much weight we can assign to different types of knowledge.

The Essay

is divided into four books, the first three laying the foundation for the

arguments set out in Book IV. Central to Locke’s argument throughout the

Essay is the idea that when we are born

the mind is like a blank piece of paper. He says:

Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we

say, white paper void of all characters, without any ideas; how comes it to be

furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store, which the busy and boundless

fancy of man has painted on it, with an almost endless variety? Whence has it

all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from

experience: in that, all our knowledge

is founded; and from that it ultimately derives itself.

What Locke is talking about here is the content of the

mind, not its abilities.

It is important to highlight this as the notion of the mind as white paper (or

as a blank slate to use another popular metaphor) is one that is still

contentious today and different people mean different things by it. Locke

clearly believes that we are born with a variety of faculties that enable us to

receive and process information (the senses, memory, our ability to use language,

explored in some detail in Book III of the Essay)

and to manipulate it once we have it, but what we don’t have is innate

knowledge or ideas.

Book I of the Essay, Of Innate Notions

is dedicated to refuting the hypothesis that we are born with imprinted or

innate ideas and knowledge, something that puts him at odds with the thought of

Descartes. But it is not just Descartes that he is refuting here. At the time

it was widely thought that certain ideas and principles were imprinted on human

beings from birth and that these were essential to the stability of religion

and morality and I think this is one reason why Locke spends so much time

debunking the notion of innateness. But there is much more to it than that.

Locke believed deeply in humanity. He was not a secular thinker, in fact he was

a devout believer in God, but he thought that the God-given faculties we

possess, especially the ability to reason, gave us a unique place in nature

which we should take full advantage of. Locke was a political animal, intimately

involved in the changes taking place in England at the time, and a great

believer in individual freedom. His was a political project and his interest in

the mind had a practical purpose behind it – he wanted to transform society and

organise it in a

rational way. His rejection of innate ideas was intimately linked to this

project for it is all too easy to claim all sorts of principles as innate in

order to maintain the status quo, meaning that people “might be more easily

governed by, and made useful to some sort of men, who has the skill and office

to principle and guide them. Nor is it a small power, it gives one man over

another, to have the authority to be the dictator of principles, and teacher of

unquestionable truths; and to make a man swallow that for an innate principle,

which may serve his purpose, who

teacheth them.”

Let’s examine his argument.

Consider for example the simple notion that it is not possible for something to

both exist and not exist. Locke argues that if such a proposition were innate

then every person in every period of history would know and understand this,

but this is clearly not the case. If such truths were ‘imprinted’ on us all

then we would expect that “children

and idiots” would not only be fully

aware of them, but also be able to articulate them. For Locke it makes no sense

to imagine both that ideas or knowledge are innate and that we do not know

them, thus in his own words: “It seems to me a near contradiction to say that

there are truths imprinted on the soul, which it perceives or understands not;

imprinting if it signify anything, being nothing else but the making certain

truths to be perceived.” He goes on to take up the suggestion that innate

propositions are only perceived under certain circumstances. The crux of his

argument is that once we start to think in this way it becomes unclear what is

meant by innate ideas at all – if we are not all aware of them nor able to

perceive them can they really be described as innate? Accepting such a view

would make it impossible to distinguish between innate ideas and new ideas that

we discover.

He also takes

up at some length the claim that innate propositions are discovered when people

come to use reason. For Locke it makes no sense to describe a truth that is

discovered through the use of reason as innate and he constructs a careful

argument to back this up, investigating and refuting different interpretations

of the claim. I do not have space here to go into too much detail here, but Locke

goes on to reject the claim that there are innate practical moral principles or

that we are born with innate ideas of God, identity or impossibility.

Book II of the Essay, Of Ideas, lays out

how human beings acquire knowledge, beginning by making a clear distinction

between different types of ideas. There are simple ideas which we construct

directly from our experience and complex ideas which are formed by putting

simple (and complex) ideas together. Locke divides complex ideas into three

types which he describes as ideas of modes, substances and

relations. Modes are

“dependences on, or affectations of substances” and relations. Thus they are

things that depend on us for their existence, including things as diverse as

the ideas of gratitude, rectangle, parent, murder, religion and politics. Substances are things in the material

world that exist independently, including what we would generally describe as

substances such as lead and water, but also including beings such as God,

humans, animals and plants and collective ideas of several substances such as

an army of men or flock of sheep. Relations

are ideas that consist “in the consideration and comparing one idea with

another.”

Locke proposes

that the mind puts ideas together in three different ways. The first is to

combine simple ideas to form complex ones. The second is to bring two or more

ideas together and form a view of them in relation to each other. The third is

to generate general ideas by abstracting from specific examples. Thus we ignore

the specific circumstances in which we gain a particular piece of knowledge,

which would limit its applicability, and generalise so that we have some rule or idea

that applies in circumstances beyond our direct experience. This interpolation

and abstraction is important in a number of areas (morality for example) but is

of course essential to science, and Locke’s familiarity with the mechanical

philosophy provided part of the reason for emphasising this way in which we generate ideas.

He goes on to discuss how sensation and reflection give rise to a number of

kinds of ideas, including moral relations and ideas of space, time, numbers,

solidity, identity and power.

By far the longest chapter in Book II is a

discussion of power and this is particularly interesting in that it provides an

opportunity to explore the notions of free will and human agency, which lie at

the heart of Locke’s political project.

Here we are not talking about power in the sense it is used in physics

(the rate at which energy is used) nor about the power one person exerts over

another, but rather in a much more general sense of an ability to make a change

(active power) or receive a change (passive power). For example “fire has a

power to melt gold … and gold has a power to be melted … the Sun has

power to blanch wax, and wax has a power to be blanched by the Sun.” Thus

“the power we consider, is in reference to the change in perceivable ideas.”

Locke’s primary

interest in power is, unsurprisingly, not related to substances in general, but

is in the abilities of human beings, in particular the powers or faculties of

the mind such as liberty, will and desire. He defines

liberty as “a power to act or not to act, according as the mind directs”

whereas the will is a “power to direct the operative

faculties to motion or rest in particular instances,” and argues that

desire is an uneasiness “fixed on some

absent good, either negative, as indolency to one in pain; or positive, as

enjoyment of pleasure.” He is careful to distinguish between these powers and

the person (the agent) who possesses

them, for these faculties are not “real beings in the soul” that can perform

actions – only the person acts. In a similar vein he argues that one power

cannot operate on another, “it is the mind that operates, and exerts these

powers; it is the man that does the action, it is the agent that has the power,

or is able to do.”

Thus for Locke the idea

of free will is nonsensical – a person can be free “to think, or not to

think; to move, or not to move, according to the preference or direction of his

own mind,” but the will cannot, for

it is simply one of the faculties of a person – the will does not think, nor

can it choose a course of action, thus how can it be free? In order to

emphasise the distinct nature of the powers discussed he points out that “there

may be thought, there may be will, there may be volition, where there is no

liberty.” For example a man falling into

water from a height “has not herein liberty, is not a free agent” since,

although he would prefer not to fall he is not in a position to act on that

preference. Similarly a man hitting a friend due to a convulsive movement of

his arm would not be considered by anyone to have liberty in this as it is out

of his control – he has no choice in the action.

Locke’s discussion of identity is also

interesting in that it explores what we mean when we think of something

retaining a particular identity. If we are dealing with an inanimate object

this is quite straightforward, we simply have to ask whether it consists of the

same matter, but if we are considering a living being things are not so

straightforward: “a colt grown up to a horse … is all the while the same …

though there may be a manifest change of the parts.” Here identity is

associated with some continuity of life of the being in question rather than it

consisting of the same matter. When it comes to humanity the question of

identity becomes further complicated and Locke makes an important distinction

between a human being (‘man’) and a ‘person’. The identity of a human being is

the same as that of any other animal, defined by “participation of the same

continued life,” but a person is “a

thinking intelligent being, that has reason, and reflection, and can consider

itself as itself, the same thinking thing in different times and places.”

Book III of the Essay, Of Words, is

central to Locke’s epistemology or theory of knowledge. He explores the

intimate connection between the names we give to things and ideas and,

following the arguments detailed in Book II, links language and ideas directly,

claiming that most words “are names of ideas in the mind.” He does deal with

other types of word, such as particles that “signify the connexion that the

mind gives to ideas, or propositions, one with the other” but his focus is on

words that represent ideas in the mind. Thus most words can be classified

according to the same categories as ideas were in Book II; words for

substances, modes and relations.

He emphasises that when we use words

they always represent the ideas the person speaking has in his or her head,

which are not necessarily the same as the ideas associated with those words in

the mind of the person listening. However, language is such that people

generally assume they mean the same thing when they use a particular word and,

further, “often suppose their words to stand also for the reality of things.”

This leads him to explore different types of words, how we understand them, and

how we use them to increase knowledge. He points out that most words are

general terms arguing that if this weren’t the case language wouldn’t be much

use for improving knowledge, for while knowledge is “founded in particular

things” it “enlarges itself by general views.” He sees words as becoming

general “by being made the signs of general ideas” and it is here that the

intimate connection between words and ideas is key.

Locke claims

that it is not possible to define the names of simple ideas, only complex ones,

since simple ideas are rooted in the things that we sense and can only be named

by reference to the things themselves: “Simple ideas … are only to be got by …

impressions, objects themselves make on our minds.” He cites the problem of

trying to define the meaning of the word light to a blind man as an example.

Without the sense of sight it is not possible to understand any definition put

forward in the way a sighted person can. Complex ideas, on the other hand, can

be defined in terms of simple ideas, provided we are equipped with all the

appropriate senses (e.g. sight) for understanding the simple ideas used. For

example a rainbow can be defined in terms of its shape, the colours it consists

of and the order they appear in.

Pointing to

the non-universal nature of words and language, Locke points out that words in

one language do not always have an equivalent in another “which plainly shows,

that those of one country, by their custom and manner of life, have found

occasion to make several complex ideas, and give names to them, which others

never collected into specific ideas.”

Locke also discusses the essence of a sort or species of idea, by

which he means “that abstract idea to

which the name is annexed; so that everything contained in that idea, is

essential to that sort.” He makes a distinction between the nominal and

real essence of a sort.

The nominal essence is the complex idea a word stands for, while the real

essence is the true properties or constitution of the thing we describe by the

word, some of which we may know, but many of which we usually don’t. This

distinction is extremely important to Locke’s overall thesis since the aim of

the Essay is to examine what we can

and cannot know. For Locke the real essence of something is not something we

can ever know, as there will always be some properties, or some behaviour that we are

unaware of. Nominal essences on the other hand will vary from person to person.

For example the “yellow shining colour, makes gold

to children; others add weight, malleableness, and fusibility; and others yet other

qualities …” However, we have to be very careful when we talk of real essences.

For one thing we only suppose their being, without knowing what they are, but

also the real essence of a substance such as gold “

relates to a sort” and thus is related to our abstractions and the

words we assign to them; “our distinguishing

substances into species by names is not at all

founded on their real essences.” Inevitably the way in which we

group substances into sorts or species is based on “their nominal,

and not by their real essences

… they are made by the mind.”

This whole account of essences, and indeed

the deliberate use of the word essence,

represents an important break from the essentialism of the

Aristotelian tradition that Locke was taught in

his youth. Aristotle believed that there are natural kinds, the essences of

which can be organised into a single hierarchical system of classification

which corresponds to the way nature is structured. Locke rejected this claim

entirely. Rather than a unique classification open to discovery by the

scientist Locke thought it useful to classify things in lots of different ways

depending on what one wanted to do. This is quite a profound difference. It

represents an important break with the thinking of the past and in this he was

clearly influenced by natural philosophers such as his old friend and mentor

Robert Boyle. Part of the reason for discussing words in Book III of the

Essay is precisely to break down the

idea of fixed boundaries between species or sorts of ideas. He says “these

essences of the species of mixed modes, are not only made

by the mind, but made very

arbitrarily, made without patterns, or reference to any real existence.” In

this he prefigures Charles Darwin, who needed to dispense with the concept of

fixed species of animals in order to establish the theory of evolution by

natural selection, by nearly 170 years!

It might seem from this discussion that Locke believed

that words never retain a common meaning when they are used by one person

speaking to another, but this is not the case. Locke, the master of common

sense, was well aware that words must sometimes signify the same meaning to

different people for otherwise there would be no communication and language

would be completely useless. However, the more complex the idea signified by

the word, the more likelihood that the word represents a different idea in the

mind of each person who hears or reads it. For the most part Locke sees

language as a tool for carrying out the pragmatic communication necessary in

everyday life. Ordinary people are the creators of language:

“Merchants and lovers, cooks and tailors, have words

wherewithal to dispatch their ordinary affairs; and so, I think, might

philosophers and disputants too, if they had a mind to be clearly understood.”

Book IV of the Essay,

Of Knowledge in General, brings to bear the arguments in the

previous books on Locke’s central question of what we can and cannot know. His

approach is to deal with what knowledge is, how we reach it, what the different

types of knowledge are and how certain we can be of any knowledge we gain. He

defines knowledge in terms of whether or not one idea in our mind agrees with

another (or others), thus it is “the

connexion and agreement, or disagreement and repugnancy of any of our ideas.”

This is significantly different from Descartes’ account of knowledge which

defines it as any ideas that are clear and distinct. Here we can see why Locke

is at such pains to make it clear what he means by ideas and their signs

(words) before defining knowledge and embarking on the central question of the

Essay. He argues that “all that we know

or can affirm concerning any of” our ideas

is, that it

is, or is not the same with some other, that it does, or does not always

co-exist with some other idea in the same subject; that it has this or that

relation to some other idea; or that it has a real existence without the mind

and that “wherever the mind perceives the agreement or

disagreement of any ideas, there be certain knowledge.”

He defines four sorts of agreement or disagreement: identity,

relation, co-existence (or necessary connexion) and real

existence giving the examples:

‘blue is not yellow,’

is of identity. ‘Two triangles upon equal basis, between two parallels are

equal,’ is of relation. ‘Iron is susceptible of magnetical impressions,’ is of

co-existence, ‘GOD is,’ is of real existence.

He distinguishes

between three types of knowledge, which have different degrees of certainty.

The clearest and most certain is intuitive

knowledge, the second most certain demonstrative

knowledge and the third sensitive knowledge.

Intuitive knowledge is

that where “the mind perceives the agreement or disagreement of two ideas

immediately by themselves, without the intervention of any other.” For example

‘white is not black,’ ‘a circle is not a triangle,’ ‘three is greater than

two.’

Demonstrative knowledge

is that where the agreement or disagreement is not perceived immediately, but

rather depends on reasoning –

following a series of steps in the mind, each of which must have intuitive

certainty, to discover the agreement or disagreement of ideas “by the

intervention of other ideas.”

Those intervening

ideas … are called proofs, and where

the agreement or disagreement is by this means plainly and clearly perceived,

it is called demonstration, it being shown

to the understanding, and the mind made see that it is so.

Because of all the

steps involved in achieving this sort of knowledge it is seen as “more

imperfect than intuitive knowledge.” This sort of proof is common in my

discipline of mathematics, but Locke is arguing that this type of reasoning is

valid in all areas of knowledge.

As an illustration I am

going to show you a simple demonstrative proof of one of Locke’s examples: that

if we add the three angles in a triangle together they are the same as two

right angles. I will not use any mathematical symbols as I know this will put

off at least two thirds of my readers, but will rather use a series of

diagrams. The idea, remember, is that each step should have intuitive certainty in order to provide proof of the hypothesis through reasoning and I hope that the example I

have chosen will carry you with it.

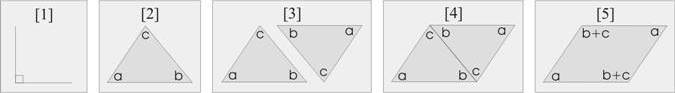

First we remind

ourselves that a right angle is the angle we find in a square or rectangle,

looking like a capital ‘L’, see [1] in the diagram below. I am only going to show you

the proof for an acute angled triangle (one with no angles larger than a right

angle), so let’s start with a general acute angled triangle as shown in [2]. If

we take an identical triangle and turn it upside down as shown in [3], then

bring the two triangles together as in [4] then we have the shape shown in [5]

which we describe as a parallelogram. We can see that each of the three angles

a, b, c in our original triangle appear twice in the

parallelogram.

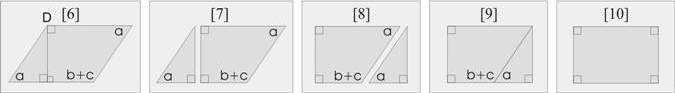

If we look at the top left corner of the parallelogram in [5] (labelled D

in [6]), I can draw a line from there to the

base of the parallelogram to make a right angle with the base as shown in [6].

Now what we have is a right angled triangle on the left and a four sided figure

on the right that can be separated as in [7]. The triangle can be moved over to

the right hand side of the diagram, where, because of the size of the angles it

will fit exactly onto the other figure, making a rectangle, see [9] and [10].

Thus we have demonstrated, by means of diagrams that

the three angles a, b, c in our original triangle, when doubled (two

triangles in [3]) have angles adding up to four right angles (in the rectangle

in [10]). Thus angles a, b and c add up

to two right angles. There are other ways of proving this, but I quite like

this diagrammatic proof by demonstration for its appeal to our intuitive

feeling for shapes and how they fit together.

The last type of knowledge Locke discusses, sensitive

knowledge, is the least certain as it is founded on objects that enter our

minds directly through the senses. Locke is well aware of the doubts associated

with trusting our senses but, ever the common-sense philosopher, argues

strongly that it makes no sense to reject the input we receive from the outside

world. We should accept that things in the external world have a real existence

even if our knowledge of them will always be imperfect:

The notice we have by

our senses, of the existence of things without us, though it be not altogether

so certain, as our intuitive knowledge, or the deductions of our reason …

deserves the name of knowledge.

Continuing on this

theme, Locke claims that it is not possible for us to discover the connection

between what he describes as the primary and secondary qualities of a

substance. The term primary qualities refers to the ‘real’

attributes of a substance, such as its size, shape and motion while the

secondary qualities are those that we

sense such as colour, taste or sound. The problem is that, while there is no

doubt a connection between these different types of quality, nothing in the

substance itself truly resembles its secondary qualities. It is simply that the

physical attributes of the substance, its primary qualities, have “a power to

produce those sensations in us.” Thus, while arguing that we should trust that

our senses provide real, if imperfect, knowledge of the physical world

(sensitive knowledge), he also severs the connection between simple ideas (in

this case secondary qualities) and reality.

This leads on to a

consideration of probability or

likelihood of truth. We have to accept the lack of certainty associated with

our understanding of the physical world because of our reliance on our senses,

but this does not mean that we cannot make rational judgements about what we

observe. Locke presents an account of probable reasoning which is very similar

to the demonstrative reasoning that generates knowledge. However, not every

step in probable reasoning has intuitive certainty, only a certain likelihood of

truth. Thus when we judge an argument or proposition as true or false we cannot

guarantee that our judgement is correct, only that it is more or less likely.

Therefore there are degrees of such judgement ranging from near certainty to

highly improbable. Locke’s discussion of probable reasoning in the

Essay does deal with things that we can

observe and experience, but his focus is on things beyond our senses including

immaterial spirits such as angels, things too small to sense such as atoms and

life on other planets, which we cannot sense because of their remoteness from

us. However, I want to draw attention to the profound importance of his points

about probable reasoning if we are to have a true appreciation of the strengths

and limits of the scientific method.

This search for knowledge through probable reasoning

is one way of thinking about what the sciences are all about –when we assess a

theory or hypothesis we balance probabilities. What is more likely? Why? At

every step of an argument we should be weighing up our level of certainty. In

general, because we are rarely dealing with ‘intuitive certainty’, the more

steps, the less certain we are of our conclusions. However, the more

experiments and observation we can perform related to each step to confirm or

refute our assumptions, the more certain we can be. This is very important to

appreciate and unfortunately is not appreciated by a lot of scientists! It is

also a huge problem for the sciences of humanity – human beings are so complex

and so different from one another that it is surprisingly difficult to

construct general arguments about humanity that hold up to this kind of

scrutiny.

So, what can and can’t we know? Like

Descartes, Locke argues that we can be certain of our own existence, this

falling into his category of intuitive knowledge, and we have “a demonstrative

knowledge of the existence of God.” Regarding “the real, actual existence

… of anything else, we have no other but a

sensitive knowledge.” However, there are areas of knowledge, such as

mathematics and morality, which are capable of demonstration and thus a high

level of certainty. This is because they are closed systems in which the rules

are created in our minds – they do not depend on input from our senses. He uses

two telling examples: ‘Where there is no property, there is no injustice,’ is

certain

for the idea of property, being a right to any thing,

and the idea to which the name injustice is given, being the

invasion or violation of that right; it is evident, that these ideas being thus

established, and these names annexed to them, I can as certainly know this

proposition to be true, as that a triangle has three angles equal to two right

ones. Again, ‘no government allows absolute liberty’: the idea of government

being the establishment of society upon certain rules or laws, which require

conformity to them; and the idea of absolute liberty being for anyone to do

whatever he pleases, I am as capable of being certain of truth in this

proposition, as of any in mathematics.

However, it is difficult to establish

certain truths in ethics because of the complexity of moral ideas and this

where the discussion of language in Book III becomes most pertinent: Locke

draws attention to two ‘inconveniences’ that are a consequence of this complexity.

First, that the words we use, the ‘names’ assigned to moral ideas, are less

precise than those of, say, mathematics, thus the idea carried in one mind by a

certain word may differ from that in another mind. Secondly, that it is

difficult for the mind to remember precisely all the relationships between

different ideas and thus, especially when several complex moral ideas are

involved, it can be very difficult to decide on the agreement or disagreement

of ideas being compared (which, remember is Locke’s definition of how we come

to knowledge). Morality does not have the advantage that mathematics has of

being able to use diagrams (and precisely defined symbols) which allow you to

review each stage of a demonstration with ease.

Following this train of thought, Locke moves

on to the extent of our knowledge “in

respect of universality,” arguing that only abstract general ideas can

provide any sort of universal knowledge:

If the ideas are abstract, whose agreement

or disagreement we perceive, our knowledge is universal. For what is known of

such general ideas, will be true of every particular thing, in whom that

essence, i.e. that abstract idea is to be found: and what is once known of such

ideas, will be perpetually, and for ever true. So that as to all general

knowledge, we must search and find it only in our own minds, and ‘tis only the

examining of our own ideas, that furnishes us with that.

Only truths belonging to abstract ideas are

eternal “as the existence of things is to be known only from experience.” This

further underlines Locke’s arguments concerning morality for “the truth and

certainty of moral discourses

abstracts from the lives of men, and the existence of those values in the

world, whereof they treat.”

He also warns against confusing ideas with

the words we assign to them as “the examining and judging ideas by themselves,

their names being quite laid aside” is “the best and surest way to clear and

distinct knowledge.”

In Chapter X Locke lays out how we can be

sure of the existence of God. I will not go into the details of his argument

here, but do think it of interest to pick out two key points that lie at the

heart of his reasoning and which I think are philosophically flawed. The first

is that it is inconceivable that there was ever a time when there was nothing –

for this he appeals to our intuitive certainty that “bare nothing” could not

possibly produce any real being. Thus there must be an eternal being “since

what was not from eternity, had a beginning, and what had a beginning, must be produced

by something else.” He goes on to reason that “the eternal source then of all

being must also be the source and original of all power; and so this eternal being must be also the most

powerful” and also must be a “knowing intelligent being,” as there is no

other way that humans, who are knowing intelligent beings themselves, could

have come into existence:

It being as impossible, that things devoid

of knowledge, and operating blindly, and without any perception, should produce

a knowing being, as it is impossible, that a triangle should make itself three

angles bigger than two right ones. For it is as repugnant to the idea of

senseless matter, that it should put into itself sense, perception and

knowledge, as it is repugnant to the idea of a triangle, that it should put

into itself greater angles than two right angles.

Like the earlier discussion of species this

argument bears an interesting relationship to ’s theory of evolution by natural

selection, which did not come along for another 170 years. provides us with an alternative: his

theory explains how a blind process can generate sense, perception and

intelligence. I discuss this at length elsewhere, but thought it worth drawing

attention to while dealing with Locke’s ideas. However, as with any of the

great thinkers, it is also worth remembering when Locke was writing and not

take it out of context. Locke believed in questioning everything and in not

accepting the authority either of the past or of the clergy. He wanted people

to rely on their own judgement

and reasoning which is precisely why he constructs an argument to

justify believing in God, and that is interesting in its own right. I will

return to this theme at the end of the chapter.

Having found the bounds of human knowledge

and certainty Locke turns to the various degrees of probability or likelihood

of the truth of an idea. This is the area of human knowledge where, in the

absence of certainty, we have to apply our

judgement. Here our minds have to take ideas to

agree or disagree or take some proposition to be true or false “without

perceiving a demonstrative evidence in the proofs.”

The highest degree of probability follows

from what our own and other people’s “constant observation has found always to

be after the same manner,” for example that fire burns. We cannot prove that

fire burns in all circumstances, but our experience and what we know of the

experience of other people gives us no reason to doubt that it will continue to

do so in conditions we have yet to come across. These probabilities rise near

to certainty and we generally don’t distinguish between them and certain

knowledge. The second degree is when “my own experience, and the agreement of

all others that mention it, a thing to be, for the most part, so: and the particular

instance of it is attested by many undoubted witnesses.” This degree of

probability, while less certain than the first degree, we tend to have

confidence in, and will generally be willing to act on as if it were fact. The

third degree, which is of course the weakest, is based on what Locke calls

‘fair testimony.’ This is when we are told that something, confirmed by

witnesses, happened at a certain time and place and, having no contradiction or

reason to disbelieve the account, we believe it.

Locke draws attention to the difficulties

associated with probabilistic reasoning, particularly when something

contradicts common experience, or when different witnesses or histories give a

different account of events. However, we should always try as best we can to

assess the likelihood of an account for ourselves and should not fall into the

trap of discounting something which is counter to our own experience – this may

simply reflect that our own experience is limited! This is good advice for any

scientist as much of science seems at face value to contradict common sense

(does the Earth appear flat or curved to you?) – it is only when we investigate

further (experiment, observation) or look at the right scale that the

properties or behaviour

of an object are revealed.

In the closing chapters of the Essay Locke makes a number of points

about reason, faith and judgement

which stand today as useful guidelines for how we should approach

knowledge. He urges us to trust our own judgement and to consider the probability of

any proposition for ourselves. He makes the interesting point that repetition

of a single testimony should give it no more weight than if it were only heard

once. His point here was primarily aimed at the word of the ancients, and had a

bearing on the general point about rejected authority and trusting oneself. It

is also another point highly relevant to the modern era, especially in this age

of instant messaging and the web, where a single testimony can be repeated a

million times extremely rapidly without any verification of facts or truth. It

is always worth distinguishing between a variety of sources confirming

something and a number of sources repeating the same rumour!

Locke is explicitly against artificially formalised types of

reasoning, attacking at length the use of syllogism, a highly formal type of

argument favoured

by Aristotle and his followers. Rather he makes the case for

argument from judgement as the only

sort of argument that brings true instruction and advances us in our way to

knowledge. He describes it as “the using of proofs drawn from any of the

foundations of knowledge, or probability.” Its validity arises from it

relying solely on reason, not on respect

for the reputation of some kind of authority, nor on accepting an argument simply

because we do not know a better one.

Locke makes a point of refuting the idea

that reason is opposed to faith, claiming that faith can never convince us of

anything that contradicts our knowledge and arguing that, except in the case of

divine revelation, we should always look first to our own reason.

Thus anything worldly and open to our own deduction,

observation, experiment or experience must always be a matter of reason. The

only times where it is appropriate to resort to faith alone is in areas not

open to our enquiry such as whether there is an afterlife or whether angels

exist.

C J M Hewett, November 2006

Source

Locke, John (2004) An Essay Concerning Human Understanding,

Penguin Classics

Top of page